Andreas Lazaris has a lot on his mind, perhaps more than the average 24-year-old American male. If you need proof of this, just have a two-hour conversation with him; it can be a fascinating and slightly overwhelming thing. He’s knowledgeable and articulate, enthusiastic and loquacious. He’s a walking, talking glossary of cognitive neuroscience. And he speaks in streams. Wind him up, let him go.

It’s understandable that Lazaris has so much to talk about. After all, the UC Berkeley graduate has spent much of his life tackling some pretty heady subjects. For years, he’s been pondering the life of the mind, a pursuit that eventually led him to also ponder the death of the mind. Memory. Aging. Dementia.

Throughout college, Lazaris worked at UCB’s Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging lab. He served as the vice chair on the City of Berkeley’s commission on aging, a position he held for two years. Post college, he worked at the University of California, San Francisco’s Memory and Aging Center. For most of his life, it seems that Lazaris’ interest in memory and aging was purely scientific. In 2014, that changed.

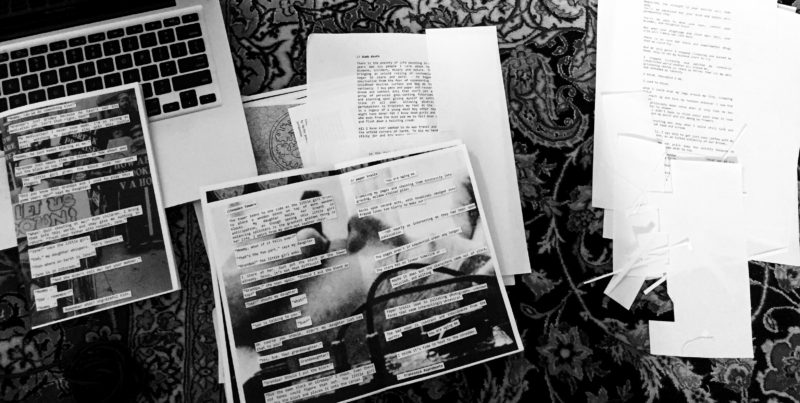

That’s the year Lazaris founded the zine “If you’d like to hear it // I can sing it for you,” which focused on the experience of aging in America. It’s a unique publication, something of a DIY literary magazine, printed on standard computer paper and stapled together by hand. It’s a passion project for Lazaris, who edits the content and designs each page himself.

In so many words, “If you’d like to hear it” is a publication that aims to give a voice to people who Lazaris says don’t always have one: the elderly, the dying. Or maybe someone suffering from Alzheimer’s disease.

“An Alzheimer’s patient does not necessarily have the ability to advocate for his or her self. Other folks advocate on their behalf,” Lazaris says, over the phone from Berkeley, on a recent Friday afternoon. “There is this need to hear from people themselves. And that idea kind of gave rise to the zine.”

The zine’s pages comprise essays, poems, and artwork submitted by people all over the country. Some are people who have experienced aging, dementia, or sickness firsthand. Some are the relatives, friends, and caretakers of those people. Different voices, different experiences.

“The way that I think about the zine is: you have these pages which are from different people who have never met each other, from different states, from different cities. And they’re all in this physical text. In a lot of ways, they’re all in conversation with each other,” Lazaris says.

Given the focus of “If you’d like to hear it // I can sing it for you,” many of the stories told within the zine are woeful, even moribund. Children recount the moments their parents succumbed to cancer. Men and women describe the onset of dementia. It’s a tableau of death, consistently powerful and assiduously difficult to grapple with. But that’s kind of the point, as Lazaris writes in the first issue.

“In these pages, we seek to understand the struggle of aging // to affirm it through inter-generational conversation. We don’t aim to busy ourselves in fabricated models of ‘productive’ aging that conceal its realities …” His aim is to offer a glimpse of the reality of aging, not some sanitized version.

Over the phone, he adds, “although something may be dark and something may be morbid or really challenging in terms of the sociological issues that it approaches and the personal and emotional issues that it approaches, I think the more difficult that it is, the more important it becomes.”

And, more than anything, he says, the zine “was created to become a space for people to be able to put things in writing and make sense of them themselves,” as an act of healing or reckoning. For its contributors, whom Lazaris says have mostly been recruited through Craigslist, the zine can be therapeutic.

If a writer wishes to be anonymous, Lazaris respects that. He also doesn’t fact-check submissions, doesn’t ask, “Is this true?” That’s not what’s important. Even works of fiction contain an amount of emotional truth.

And since the zine is purely a print product, contributors don’t have to worry about their personal accounts being cataloged in online search engines. The zine is available to be ordered on Tumblr and Facebook, but the stories contained within each issue can only be found in print. This helps preserve anonymity.

The zine offers “a way to really express these things and send them out into the ether,” Lazaris says. “And someone might read them. Someone might not. But it becomes a little more cathartic, it seems, for some people to just send it out and to not really think about what happens to it.”

Think of the zine as a message in a bottle, cast out in a sea of libraries and independent bookstores. “It gives people a lot more freedom to be as open as they need to be or as they want to be, in a way that they themselves and the role that they hold in the world [aren’t] attached to the story,” he says.

“If you’d like to hear it” has its benefits for Lazaris as well, in ways both personal and professional. For one, he shares some of his own experiences in the zine, most notably the death of his grandfather, who passed away a little more than a decade ago, the day after Christmas.

His grandfather’s passing “was the first time that a death affected me the way it did, because it was a person who was so close to me and it was the first of the grandparents, the first of the elders of the family to go,” Lazaris says. “And I think that being the first, it was an impactful moment, and it influenced the way that I thought about [how] elders should be treated and interacted with in our society.”

He felt it was important to place some of his own writing in the zine, as an act of harmony. “By including a personal story and a personal reflection and opening up that part of myself, it was kind of in solidarity with the rest of the contributors who open up a part of themselves,” he says. “I think it would be unfair to say, ‘I’m the curator … but I won’t open myself up to uncover the same burdens that these contributors have.’ ”

Professionally, the zine offers Lazaris invaluable insight into the lives of the aging, insight he’ll be able to apply during his career. About a week after our phone call, Lazaris moved to Providence, RI, where he’s attending medical school at Brown University. He intends to be a geriatrician.

“One of the things that [the zine] does for me is helps me to think about these issues even more,” he says. “Because I’ve had a certain set of experiences within aging and caring for people, both family members and patients in the various places that I’ve spent time in. But those are just my experiences.” Working on the zine “really gets me to think about my life and my place in this work and in this field.”

For more information on “If you’d like to hear it // I can sing it for you,” visit agingzine.tumblr.com.