When I was ten years old, my mom and I went to see the doctor because my grandfather was sick. He had been there for me countless times when I got sick as a kid, and I wanted to be there for him now. Pop sat on the exam table crinkling the thin white paper beneath him while my mom and I sat in chairs and looked at framed diagrams of organs on the walls. When the doctor came in, we all stood. He started with a battery of questions I could barely follow. Then he asked my grandfather, whom I called Pop, about me. “Who came in with you today?”

“I don’t know,” Pop said with a tilt of his head that made us all smile.

“Who’s this?” he nodded towards my mom.

“Karen,” he said with a wry grin. “Of course I know who my own daughter is.”

“And who’s this handsome fellow?” All the eyes in the room turned on me.

“Never seen him before in my life.” All four of us laughed for a moment. Then the doctor pressed.

“Joe, is this your son?” My mom rested a hand on the back of my neck. She must have begun to feel nervous.

“No, that’s not my son.” Good, we all nodded. But then he continued. “He’s a stranger.”

My mother choked out a laugh, but this time she was the only one. “Come on, Pop,” she strained to smile, “I know you know who this is.” But he did not.

“He’s a stranger and I haven’t seen him before.” No one was laughing or smiling. My throat burned with shame.

“Pop, it’s me.”

“Dave,” my mother interrupted, “It’s okay he’s just joking.”

“It’s me.” But Pop folded his arms and turned his attention back to the doctor for more questions. Though he was unbothered, I saw fear in my mother’s eyes. My legs hung from the hard armchair and as soon as I started to cry, my mom scooped me out of the room. Before the door closed behind me, I heard my grandfather say once more: “Never seen him before. Total stranger.”

At ten years old, I just wanted my grandfather to stay the way that he was. Following the appointment where he failed to recognize me, I was determined to help him get better, which meant finding ways to get his memory back. I thought I could reverse his memory loss by flooding him with more memories. After school, I would go to my grandparents’ Manhattan apartment to comb through photo albums. For years, he would sit at the head of his dining room table with me flipping pages by his side. When memories burst forth, they felt like breakthroughs. Over time, I came to recognize these moments as mere blips. I became a stranger in his house. Sometimes he would yell at me to leave and my grandmother would have to calm us both down. He lived like this for ten excruciating years until he died surrounded by family.

Watching my grandfather go through this experience led me to try to understand more about this Alzheimer’s disease and how it impacts families. I went to college and majored in neuroscience. I began working at the Penn Memory Center so that I could spend time talking to patients with dementia and their caregivers. I got a crash-course in what goes right and what goes wrong in dementia care.

When someone starts to lose their memory, there is usually a rush to recover the past. When this fails, as it always does when a person develops dementia, the gap created by a lack of memory can be filled with a lot of things—in my family, it was filled with silence. For some families, that silence is not benign. In the silence, the person with dementia can feel a crushing pressure to remember. It can lead to shame and embarrassment. People in these situations can be marginalized by isolation, stigma, and in more severe cases, by chemical restraints via anti-psychotics. Too often, the story ends with patients siloed into nursing homes with staff who are too busy, leading to downward spirals of isolation, dehumanization, and residents clinging to wisps of autonomy.4 Older adults who perceive aging in this context can have negative thoughts about growing older and this has dire consequences on long-term health. In a study designed to target how older adults understand aging and associated stereotypes, researchers showed that negative self-images about aging among the elderly were associated with an average loss of 7.5 years from life expectancy.5

After college, I began medical school at Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Jefferson University so that I could learn how to take care of patients, like my grandfather, who are suffering from dementia. Midway through my first semester at Jefferson, I saw a poster for a meeting about creative approaches to dementia care. I couldn’t resist. In the presentation, I met a woman named Anne Basting who spent the next hour disrupting my textbook understanding about how to deliver creative care to patients with dementia.

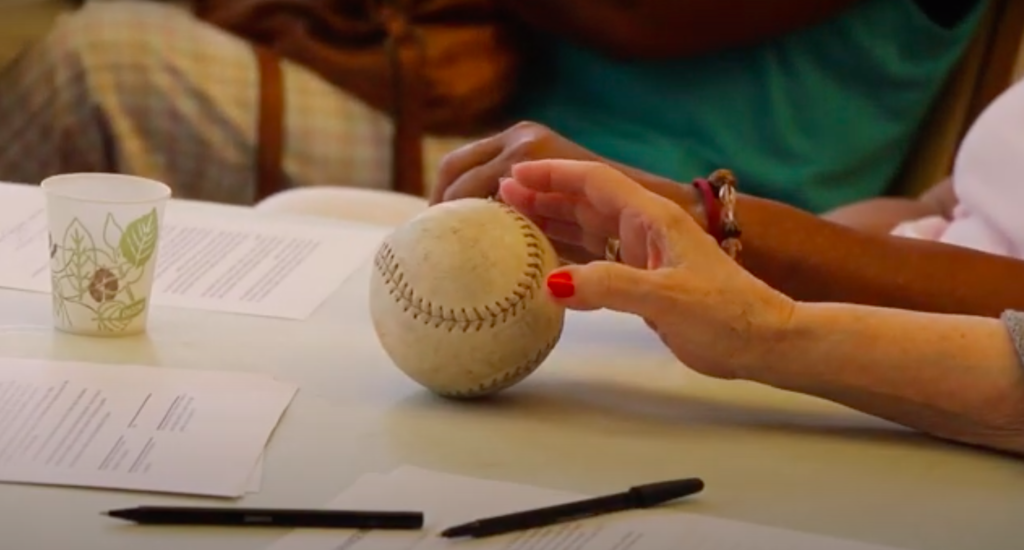

In 1995, Anne Basting founded TimeSlips as a way to connect to older adults with dementia. She scrapped the concept of pushing patients to remember their past. Instead, she focused on creating spaces and tools for people with dementia to create new ideas. Using historical or silly photos and objects, TimeSlips leaders ask open-ended questions to the participants. The result: people with dementia generated stories that sounded like personalized Mad Libs comics. Today, TimeSlips operates in 20 countries and all 50 United States. Anyone can become a facilitator by completing an online course. Any room with enough seats can be transformed into a session. The method has been praised for its positive impact on facilitators and participants. Researchers have found that participating in or leading these sessions improves medical students’ attitudes towards people with dementia.1 For the participants with cognitive impairment or dementia, it has been shown to boost joy and increase quality of life.2,3 In its most simple form, it’s an activity that a caregiver and a person with dementia can enjoy when they are together. On a larger scale, it can be a reoccurring group activity that brightens an assisted-living facility.

The first time I witnessed a TimeSlips session, I thought I had seen a miracle. I could not believe that the people around me had dementia. They were cracking jokes way faster than I imagined they would. My cheeks ached from smiling for the entire session. Afterwards I thanked the participants for letting me observe their humor, grief, and joy for nearly two hours. When we hugged goodbye, they urged me to keep coming back. I felt like I had been initiated into a club. I wanted to try to capture the energy I had seen and share it with my friends, my classmates, and my family. I wanted them to know that good people were taking creative approaches to dementia care that might make living with this disease just a little bit more bearable.

*

While no two TimeSlips sessions are ever the same, the session that I filmed stands out. Most of the participants in this activity do not have dementia even though the typical TimeSlips participant has some level of cognitive impairment. They come from a variety of backgrounds of people who are cognitively normal, have Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), or slightly more advanced stages of dementia. Anyone in this film who has cognitive impairment is accompanied in this video by a caregiver—either on camera or in the room just outside the circle. They all agreed to appear in the film and documented their consent in writing. Those with cognitive impairment signed additional waivers and had their caregivers sign additional waivers too, explaining that they understood they were appearing on camera and that this film would be used for educational and advocacy purposes. However, I will not tell you who has dementia or how many people have a diagnosis. I suspect that you will not be able to determine who is cognitively normal and who is not. In this small circle of reminiscence and storytelling, I think you will know who is mischievous, who is nostalgic, and who is watchful—but that just illustrates the TimeSlips perspective that allows us to peer into the minds of the participants and helps us form connections.

The sessions that I’ve led at Jefferson begin with the refrain: “There are no right ideas or wrong ideas, only your ideas.” TimeSlips has redefined what dementia means to me and it has changed how I support people with this disease. Now, when patients do not remember my name or cannot follow along in a conversation, we forge forward and forget about the pressures of who remembers what. We laugh and make up stories and find new ways to connect.

The world as it is in 2020 does not offer cures for dementia, but TimeSlips offers something else. Particularly in a time where many of us are confined to our homes and our typical routines are disrupted, new caregiving practices can be an important reprieve. For caregivers living with a person with a person with dementia, TimeSlips resources on their website can be an effective way to shake up a routine. If you have a loved one with dementia who is far away from you and you cannot connect with them physically, some of the stories and principles from TimeSlips may help you both laugh and enjoy each other’s company over the phone or video chat.

For me, TimeSlips is an example of where I hope dementia care can go. It offers playfulness to brighten a disease that is so often cloaked in fear. If I were sitting on Pop’s couch today, I would put away the old photo albums and pull out zany pictures or objects. If I could re-do how we spent our time, I would not force old memories out of him, but work to create new ones together. As someone who cares for others with dementia, it forces me to consider: if this were me, what would I want? If dementia comes for me, I know that I will still want to find meaning in my life. I would want to have fun, be able to laugh, and find companionship, however fleeting those feelings will be. I would want to be known as more than a disease. I would want to know that there are people doing everything they can to help me enjoy life.

References:

1. George DR, Stuckey HL, Dillon CF, Whitehead MM. Impact of Participation in TimeSlips, a Creative Group-Based Storytelling Program, on Medical Student Attitudes Toward Persons With Dementia: A Qualitative Study. The Gerontologist. 2011;51(5):699-703.

2. Swinnen A, de Medeiros K. “Play” and People Living With Dementia: A Humanities-Based Inquiry of TimeSlips and the Alzheimer’s Poetry Project. Pruchno R, ed. The Gerontologist. 2018;58(2):261-269.

3. Vigliotti AA, Chinchilli VM, George DR. Evaluating the Benefits of the TimeSlips Creative Storytelling Program for Persons With Varying Degrees of Dementia Severity. Am J Alzheimers Dis Dementias®. 2019;34(3):163-170.

4. Blass DM, Black BS, Phillips H, et al. Medication use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(5):490-496.

5. Levy BR. Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.