Philip Marshall turned in his father when he suspected financial abuse of his grandmother, Brooke Astor — “the First Lady of Philanthropy.” Since then, he’s turned a background in historic preservation into a passion for elder justice. He sat down with Making Sense of Alzheimer’s Dr. Jason Karlawish to discuss his path.

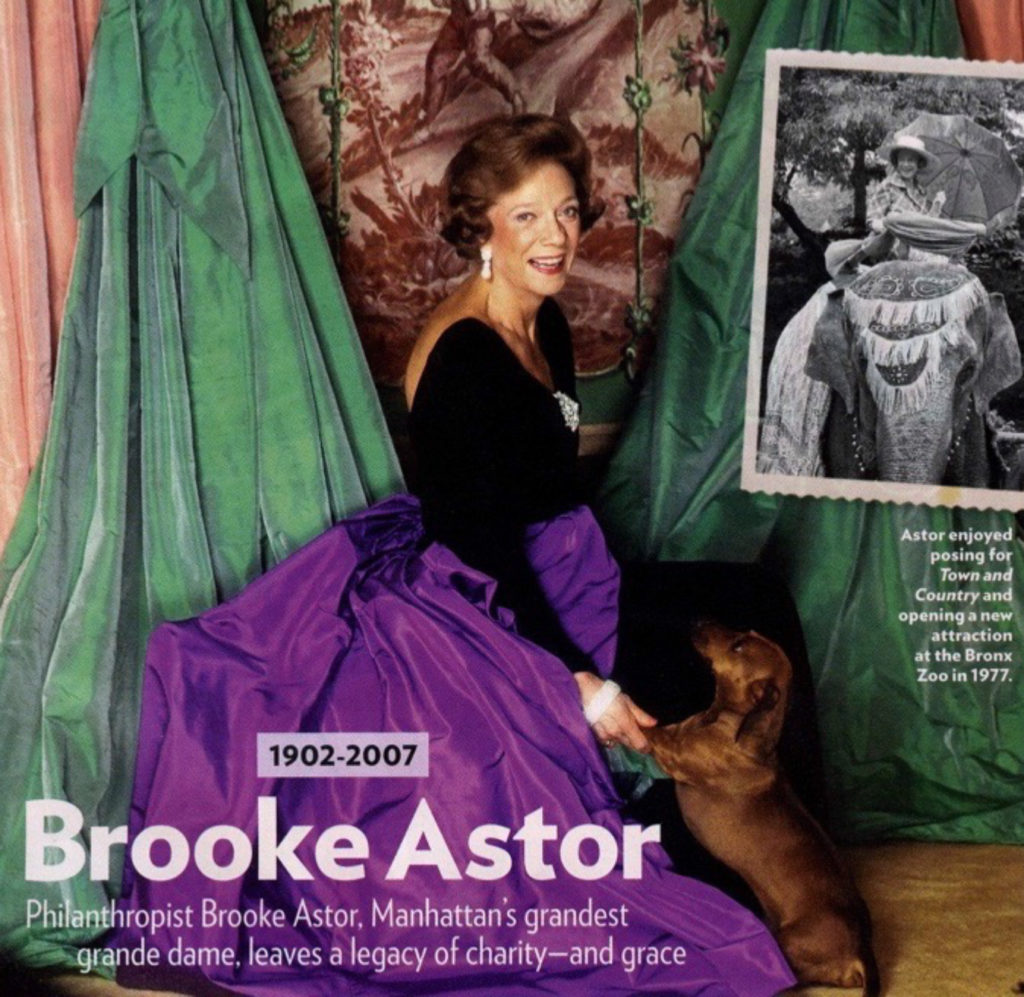

In her signature white gloves and elegant hat, Brooke Astor was known throughout the 20th century for her kindness and extravagant generosity. When she passed away in 2007 at the age of 105, the New York Times called her the “The First Lady of Philanthropy” for the millions of dollars she invested in New York museums, libraries, shelters, and community programs via the Vincent Astor Foundation.

With generous acts and a contagious energy, she devoted herself to the preservation of cultural centers including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the New York Public Library.

Mrs. Astor had a sparkling group of friends that included former First Ladies Nancy Reagan, Jackie O, and Lady Bird Johnson; as well as prominent leaders of government, media and finance, like Henry Kissinger, Barbara Walters, David Rockefeller, and many more. Her favorite designer, Oscar de la Renta, was married to Annette de la Renta, one of Mrs. Astor’s closest friends.

A proud centenarian, Mrs. Astor maintained her own dignity with beloved dresses, art, and distinguished company. But as she accumulated birthday celebrations, it became apparent to those around her that her health was rapidly deteriorating.

Her son, Anthony Marshall, was guarding a secret. Throughout her 90s Mrs. Astor’s behavior grew erratic and irregular: she would get lost on her own properties, she lashed out at longtime assistants. Friends who visited her said that she would repeat herself and would get confused often. Her staff was worried about her. In the year 2000, just months before her 100th birthday, she reluctantly agreed to see a neurologist with Anthony where she received her painful diagnosis: Alzheimer’s disease.

As her disease progressed, her relationships suffered. She tried to maintain her social life but had nurses accompany her on all outings. Over a four-year period, nurses filled up 30 notebooks that portrayed Mrs. Astor as a woman in despair. Anthony’s presence in her life was constant, and Mrs. Astor’s staff said that he often made her unhappy.

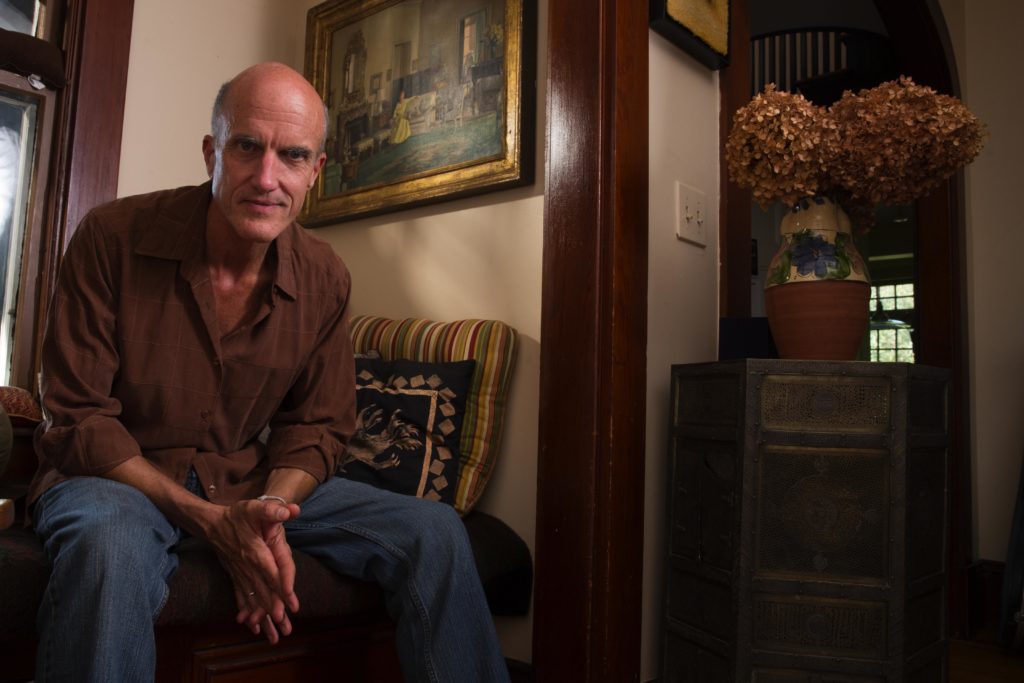

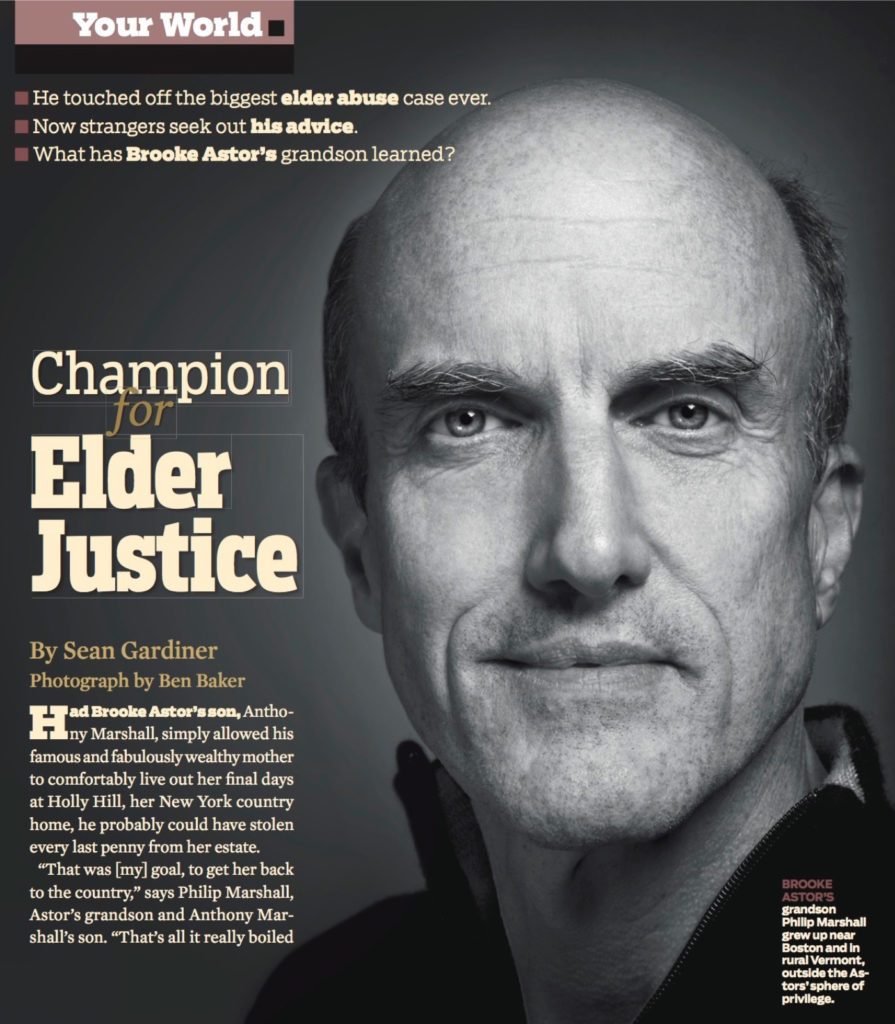

Philip Marshall, Anthony’s son and Mrs. Astor’s grandson, took notice of his father’s harsh attitude towards his grandmother, ultimately discovering a pattern of neglect and financial abuse. He became the central figure in protecting and preserving Mrs. Astor’s dignity at the end of her life. His painful experience would transform him into a passionate advocate for elder justice.

A Historic Preservationist

Since 1990, Mr. Marshall has been a tenured professor at Roger Williams University. The combination of his undergraduate degrees in geology and studio art, a Master’s in historical preservation, and experiences in construction and preservation made him uniquely qualified for work in the field of historical preservation.

Meanwhile, his grandmother’s philanthropy work also had become engaged with community preservation. Each charting their own course, grandson and grandmother found themselves on similar paths to protect and defend beauty wherever it was.

What combines the two passions, historical conservation and elder justice, that have defined Mr. Marshall’s career?

“Both deal with the ageless value of that which is old, but which may be discounted,” Marshall said, “sometimes until it is too late.”

His unique educational track suited him nicely for work in historical preservation. That experience of dealing with delicate, aging beauty situated Mr. Marshall to save his grandmother from further abuse.

A signal moment for Mr. Marshall came in January of 2006 when he went to visit his grandmother.

Defying his father’s previous request to be present during visits, “I snuck in with the help of my grandmother’s staff and caregivers, sat down with two nurses, and they just explained how wrong things were. I didn’t need to look far. The place was cold, the parquet floor on the dining room was the litter box for the dogs, and there was what I’ll now call medicinal deprivation. Nurses were taking money out of their pockets to buy things for her.”

Mr. Marshall saw deterioration and he saw abuse. He looked to his grandmother for inspiration. He searched his own mind and background and knew that he had to act. He and his grandmother had a shared passion for preservation, and those instincts, from years of schooling, kicked in.

Mr. Marshall began reaching out to his grandmother’s inner circle. He sought guidance from David Rockefeller and Annette de la Renta who both graciously took to Mrs. Astor’s defense and offered legal counsel and emotional support. Together they provided affidavits and helped Mr. Marshall prepare a petition for guardianship. Mrs. de la Renta and J. P. Morgan Chase would be appointed guardians.

In a high-profile criminal case that persisted for years, Mr. Marshall accused his father of stripping Mrs. Astor of her dignity for his own self-enrichment by siphoning money from income from her estate and by selling her artwork, notably her favorite painting by Childe Hassam (right). Her son, claiming they needed more money despite Mrs. Astor’s annual income of $5 to $6 million, sold the painting for $10 million and took $2 million in commission for the sale. Afterwards, Mrs. Astor asked her son, “Now can I buy dresses?”

In a high-profile criminal case that persisted for years, Mr. Marshall accused his father of stripping Mrs. Astor of her dignity for his own self-enrichment by siphoning money from income from her estate and by selling her artwork, notably her favorite painting by Childe Hassam (right). Her son, claiming they needed more money despite Mrs. Astor’s annual income of $5 to $6 million, sold the painting for $10 million and took $2 million in commission for the sale. Afterwards, Mrs. Astor asked her son, “Now can I buy dresses?”

Mrs. Astor died in 2007 at the age of 105. Two years later, along with 70 other witnesses, Mr. Marshall testified against his father in criminal court. The charges included grand larceny, criminal possession of stolen property, forgery, scheming to defraud, falsifying business records, offering a false instrument for filing, and conspiracy. Ultimately, the jury convicted Anthony Marshall of grand larceny and up to three years in prison. He served three months before being released for medical reasons.

Anthony Marshall died in 2014.

An advocate for elder justice

It is evident from the guardianship filed for his grandmother (and against his father) that the grandson of a wealthy New York City socialite could have benefited financially from staying silent. But that was never a consideration for a grandson who followed the example of a grandmother who had become a national symbol for elder justice in addition to her illustrious career as a philanthropist.

“For about four decades she practiced philanthropy as an elder and recognized that philanthropy is the priceless meaning of humanity. And through that lens of humanity I think we can break through ageism by example. Seniors are not the ‘problem,’ ” Mr. Marshall said. “They are part of the solution.”

Typically, the topic of elder justice arises following a case of elder abuse. But Mr. Marshall frames seniors as the solution to ageism and prefers his advocacy to focus on optimism by emphasizing elder justice over elder abuse. When people ask him if he’s combating elder abuse? He says no, “I’m advancing elder justice.”

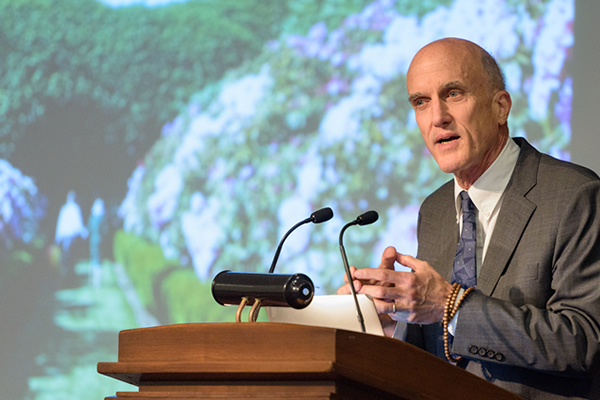

What exactly is elder justice? Years passed while Mr. Marshall reflected on what the term meant to him as a man who fought for justice on behalf of his grandmother.

As a leading advocate for a nationwide push to promote elder justice, Mr. Marshall has helped redefine the term.

“I was trying to create an absence of tension for my grandmother. In seeking guardianship I was trying to help my grandmother and help those who were helping her. It was only last year where I realized that’s only half of elder justice: we’re helping elders. That’s fine. The justice involves, not only was I helping my grandmother and those who were helping her, but I was bringing my father to justice,” Mr. Marshall said.

Combatting ageism, supporting elders, and seeking justice. These are just some of the many components that he now draws upon in his evolution from a grandson focused on preserving his grandmother’s dignity to an advocate advancing a national cause.

Being complacent is as wrong as being complicit, so he does not sit idly knowing that others are suffering, he said.

Integrating wealth and health

In many ways, Brooke Astor was exceptional. However, she was also just another member of the population who are typically at risk for financial scams and exploitation: older adults.

Normal forms of aging can cause cognitive decline, but neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s can dramatically affect a person’s ability to handle their own daily life chores, including managing their finances. Early detection of changes in financial acuity can put older adults in a better position to protect their savings. Nobody wants to lose money because of an ill-advised financial decision or because they are targeted by a financial scammer.

One potential solution put forward by Dr. Jason Karlawish, the Director of the Penn Neurodegenerative Disease Ethics and Policy Program and the Co-Director of the Penn Memory Center, is to encourage the intersection of financial and healthcare institutions.

Karlawish introduced the term “whealthcare” to address the inseparability of a person’s health and financial standing in today’s world. Health, wealth, society and the self all must merge seamlessly in order to protect and preserve an aging population.

Mr. Marshall believes that the financial industry could have detected and quite possibly prevented his grandmother’s abuse.

Banks can detect changes in financial activity with ease. When someone leaves the country without telling their credit card company, the card gets put on hold when there’s a purchase. When someone who spends a consistent amount each month suddenly makes two massive purchases, their bank will be made aware of this activity. These types of interventions have become the standard. Further steps in this direction are key to protecting older adults.

As was the case with Mrs. Astor and her son, it is a fact that friends and family often perpetrate financial fraud and abuse. One way to combat this is to allow banks as well as designated family members to be able to monitor the account in a view-only mode. This puts financial professionals in the position to detect a problem and then reach out to clients if they need guidance.

Another specific financial intervention would include collecting names of trusted individuals that banks can contact if, for example, the account holder calls the bank multiple times throughout the day to execute the same transaction. Banks can enact policies that are in line with common sense that helps older adults remain financially secure.

Living in the throes of Alzheimer’s disease, Mrs. Astor was a vulnerable target. But her grandson insists that despite her immense wealth, at this stage in her life she was making transactions that the financial industry could have monitored to tip them off to the millions of dollars being siphoned out of her account.

“There are probably six forms of abuse, but the top two — based on reality — are elder financial exploitation and emotional or psychological abuse,” Mr. Marshall said. Although he was aware of the psychological abuse, financial institutions could have played a significant role in bringing attention to the financial exploitation.

Tragically, no such alert system was in place for Mrs. Astor, and businesses did not feel financially or ethically compelled to intervene. However, financial institutions and security agencies are changing. Mr. Marshall noted, ticking off names like FINRA, NASAA, SIFMA, and CFPB, that more players have positioned themselves to support elder justice.

The story of the last years of Brooke Astor’s life is a sad one, but her grandson’s courage has helped to forge new possibilities for the elderly. The arc of history bends towards justice and in the years since Mr. Marshall has become a public advocate for elder justice, true progress has been achieved.