“Alzheimer’s Stories” begins methodically. Brass instruments in staccato are joined by soft percussion and the xylophone in a clean and structured introduction, leading the way to the chorus’s solemn repetition a few minutes later: “Ich hab mich verloren.”

I have lost myself.

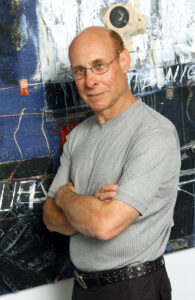

Over a decade ago, when the Susquehanna Valley Chorale approached composer Robert Cohen to create a very specific musical work, he wanted to say no. An anonymous member of the chorus had put up a substantial donation toward a piece in memory of their parents who passed away with Alzheimer’s disease.

“It was a very odd sort of situation. In a million years, I wouldn’t think of writing a piece about Alzheimer’s disease,” Cohen said. “But then I started thinking about it and I said to myself — you know, because that’s sort of my personality — ‘That’s the very reason to do it. Because nobody else would do it.’”

Following its premiere in 2009 at the Weis Center for the Performing Arts in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, the critically acclaimed “Alzheimer’s Stories” has been played nearly 50 times nationwide. It is one of the most performed classical pieces of its size, with a choir of 50 to 200 voices and an instrumental ensemble, in the country.

“It has sort of become my signature work,” Cohen said. “It actually astounds me. Even my undergraduate composition teacher, who I still send every work of mine to, said, ‘It’s a great piece. Maybe you’ll get two or three performances.’ And I’ve had like 40 performances already, just for a piece of contemporary classical music, which is very unusual.”

“Alzheimer’s Stories” follows the history and experience of Alzheimer’s disease, marking its recognition in 1906, narrating the recollections of chorus members and friends who have experienced Alzheimer’s disease, and paying tribute to the caregivers who care for loved ones with the disease. Cohen composed the music alongside Grammy-Award-winning librettist Herschel Garfein.

“When [Cohen] called me up and asked if I was interested, I said, ‘No way,’” Garfein said. “I remember saying, specifically, ‘Run away. Just turn and run from this, because it’s too difficult a topic.’ And, I personally felt like I could never do it justice.”

Garfein and Cohen had previously collaborated on a musical work dramatizing the life of Thomas Edison, titled “Edison Invents.” Cohen invited Garfein to be a part of the project because “I thought he was the only one who could do the subject justice.”

While on a drive back from Lewisburg, Pennsylvania where the two artists met with the chorus members of the Susquehanna Valley Chorale, Garfein was struck with the idea to use the true experiences of many of the millions of people whose lives are pervaded by Alzheimer’s disease.

“I had this idea that, well, instead of my trying to come up with some words on this subject that I felt ill-equipped to tackle, I thought, ‘In any given community in the United States, so many people are affected by this disease. Let me get the words from them,’” Garfein said. “That was definitely the turning point in the piece.”

A private blog was designed to allow members of the chorus, as well as family and community members, to contribute their own accounts of their experiences with the disease. Nearly 70 submissions were received over the course of a few months.

“It was really remarkable because the level of detail, emotional honesty and the level of insight in what these people said was just a dream come true,” Garfein said. “What I really admire and love in language is the sense of what I think of as inadvertent poetry. When somebody expresses themselves so clearly and so honestly, that it has a kind of poetic sparkle to it. In these accounts, I found all these remarkable things that, you know, ended up in the piece that these people just said, because they had been through it, and they knew what it was.”

“Alzheimer’s Stories” is divided into three movements in an effort to capture three different perspectives and follow the arc of the disease, from consciousness to unconsciousness. In classical music, a movement is a self-contained section of the larger work.

The first movement — “The Numbers” — sings of the conversation between Dr. Alois Alzheimer and 51-year-old Auguste Deter in 1901. Deter was a patient at a mental asylum in Frankfurt, Germany, who showcased symptoms such as short-term memory loss, reduced comprehension, and psychosocial impairment. Dr. Alzheimer followed Deter until her death five years later, and continued to study her brain after her death. With his colleagues, he identified amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles — now known as biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease.

“A very, very happy internet discovery, early on in the process, was that I found a transcript of the original conversation — sort of the intake interview — between Dr. Alzheimer and his first patient, suffering this unique premature loss of memory. And I just took that verbatim off of the internet, and we used it as lyrics in the first movement,” Garfein said.

Borrowing from notes on the conversation, it follows the spread of the disease and awareness about it, interspersed with numbers detailing the number of people affected by the disease in the past, present and future. Garfein describes the movement as a synopsis of the epidemiology of the disease.

“He made the first movement very clinical,” Cohen said. “It was very objective. It was taking the data and the information, and spreading it out. And that’s why, musically, I tried to create this piece that was very rhythmical and very well organized.”

It is followed by “The Stories” — the second movement that explores the behaviors and moments of memory loss among patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. It employs theatrical elements to invoke feelings of wistfulness and loss as it narrates critical moments of cognitive impairment.

A few stories are entwined in the movement. The chorus sings of a son who watches his father take apart an RV but cannot remember what to do next; a mother who blacks out while driving her daughter home; an old man who repeats his stories from the Navy, forgetting that he has just told them; and a mother who sits in a nursing home but believes she is on a boat to Panama.

“I felt very moved and very convinced by specific details in the stories,” Garfein said. “Bob and I talked about the fact that our obligation was to derive as much personal meaning from those stories as we could, without explaining them. To just honor the people who went through those things.”

One of the stories weaved into the movement was of a woman, who remained anonymous through the creation of “Alzheimer’s Stories.” She visited her father weekly in the nursing home to sing to him a song from his past. One week, she was out of songs to sing. But her father pleaded with her to simply sing. “Sing anything,” he had said to her.

“Sing anything” triggered the third movement for Garfein, who cannot recall the story without tears in his eyes.

The third movement — “The Caregivers” — is dedicated to the people who care for their loved ones with Alzheimer’s disease.

“It was so clear, even when they didn’t even enter into their own accounts but were talking about their parents and their loved ones, how important they were in the treatment of this untreatable disease,” Garfein said. “They are the heroes. They are the people who are making the end of life comfortable for people suffering from this terrible disease.”

The Alzheimer’s Association found that more than 11 million people nationwide provided approximately 15.3 billion hours of unpaid care for people with Alzheimer’s disease and other related dementias in 2020.

The story of the woman singing for her father served as proof of the restorative function of music for the composers and it became the touchstone for the last movement.

“This was perfect. I cried for two days and said, ‘Oh my god, this is like perfection,’” Cohen said. “The real irony to this whole thing is that it wasn’t until several years later that research started coming out indicating that music does have this palliative element to it that people who don’t know who they are, where they are, where their kids are, will be able to sing back a song that they learned when they were five or six years old perfectly. It’s really astounding. […] It gives me chills.”

Darina Petrovsky, PhD, RN, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing studying the cognitive effects of music among older adults with mild cognitive impairment to develop music-based intervention methods, said that music improves mood, temporary cognition and the ability to recall events surrounding a specific type of music among older adults.

Over the last decade, public interest in the role of music in cognition has increased and has led to expanding research in the field. According to Dr. Petrovsky, a 2015 study published in Brain: A Journal of Neurology evidenced the sustained effect of reception and performance of music well into the advanced stages of dementia. The study found that the areas responsible for music perception were less affected by the different pathology and atrophy in the brain.

At the first performance of “Alzheimer’s Stories,” Cohen was approached by a man, a foot taller than himself, who bent down nearly halfway to wrap his arms around the composer. The musical piece had brought the man to tears as it reminded him of his mother’s own experience with Alzheimer’s disease.

“I’ll never forget it,” Cohen said. “He said, “My mother has Alzheimer’s and until I heard this work, I never thought I could deal with it. Thank you.’ And, that to me, is, to the day I die, is the greatest compliment I have ever received for anything I’ve ever done.”

In the last three years, Garfein lost one of his parents and both of his wife’s parents. Writing for “Alzheimer’s Stories” over a decade ago, he believes, taught him the best ways to spend time with and provide comfort to his loved ones.

“There was this remarkable account we used in the third movement. There’s one moment where somebody said, ‘Her fingers looked like dancing.’ I had no idea what that meant. And then, I saw it in my mother-in-law when she was very close to the end. Her hands would make these gestures like [dancing],” Garfein said. “The specificity and universality of those accounts really made the piece worth doing and hopefully, make it worth hearing now.”

“Alzheimer’s disease” has become a part of Cohen and Garfein’s legacy. For Garfein and Cohen, being known for this piece, upon seeing the impact it has had on hundreds of families across the country, is an honor.

“I remember, when I was doing real estate, a woman I worked with closely said, ‘What would you like on your gravestone?’ […] I said, ‘I want it to say he moved people,’” Cohen said. “I think that’s what the piece means to me. I’ve never had a response to anything I’ve ever written that has been as profound as the response I get to Alzheimer’s Stories. And that’s a great honor. It’s a great feeling of achievement.”

Befittingly, the line to carry the piece through to the end sings, in a cathartic crescendo, “Love and music are the last things to go. Sing anything.

“Sing.”