My dad grew up in the dry deserts of Arizona but always yearned for salt water and waves. Here he floats in the waters of Barnegat Bay, NJ, during a family kayaking trip in May 2015. (All captions written by Cheney Orr.)

Cheney Orr had never planned to chronicle his father’s dementia.

In the early stages of decline, Cheney was simply doing what he always did: taking photos of the things that were happening around him, of his family.

“I didn’t start documenting it intentionally, let’s say. As a photographer, I have my camera with me almost all the time,” he said.

As the disease progressed, and a project began to form, Cheney used his camera to remove himself from the emotional, raw situation. He could distance himself from difficult moments, behind the camera.

Taking the photos brought the reality of the situation to life for him. He saw his father, his father interacting with his family, his father interacting with the world, and his father’s frontotemporal dementia, through the lens.

“Basically, that all changed for me as the disease worsened,” he said. “I would say, at that point, the camera became more of a shield. . . Whereas before, it was making me more aware of what was going on, and upsetting me more, when the disease had basically taken control, where there is no denying it at a certain point, then it became a shield. That was my process through things.”

The camera became more of a shield.

David struggles to keep up with the conversation during a dinner with family and friends in December 2016. My dad had always been extremely social and friendly, taking great pleasure in chatting one-on-one whether at the grocery store, in the locker room, or with the UPS delivery man. But group dinner table conversations were difficult, even in the earlier stages of the disease, and became especially stressful as it progressed.

Cheney took the photos over about three years. The earliest images were taken in 2014 or 2015. David, Cheney’s dad, died in May 2017. All of the images were taken on film and developed in Cheney’s home dark room.

“In the dark room is where I fell in love with photography, and watching images appear almost like magic,” he said.

The photos show moments of normalcy and happiness. In a few, David is swimming, something the duo did monthly. He was a competitive swimmer in his youth. Though David’s pool etiquette was lacking from time to time, these were moments of enjoyment, ripping through the water in freestyle and butterfly. Cheney explained that, faster than most in the pool, David may bump into people or not wait his turn. In these instances, Cheney would apologize for him and then join David.

Another image shows David dancing with a stranger to folk music. Others show David with Cheney’s brother and sister.

David could dance and especially loved country swing. But just about any kind of music with a good rhythm or beat would set his body seamlessly into motion. Here he dances with a stranger to live folk music on Governor’s Island in the summer of 2016.

The series fits in with Cheney’s body of work, which includes images from the Ukraine and also around New York City. His interests lie in long-term documentary and social issues.

“Having this work published and getting the reactions and feedback that I have, and feeling it’s had an effect on just one person — or multiple people — I want to do it again, with other stories and other issues,” he said.

The project was not something he shared with his family until it was close to publication. Cheney said he was apprehensive and not sure how they were going to feel, but all of his family members gave their support.

At times, he questions whether it is what his dad would have wanted.

“My dad was always kind of shy with the camera. Generally, when I would take pictures of him, he’d make silly faces … he was very aware of me taking pictures. As the disease progressed, his awareness of me — he was still aware but, it was a different kind of awareness: quiet acceptance.”

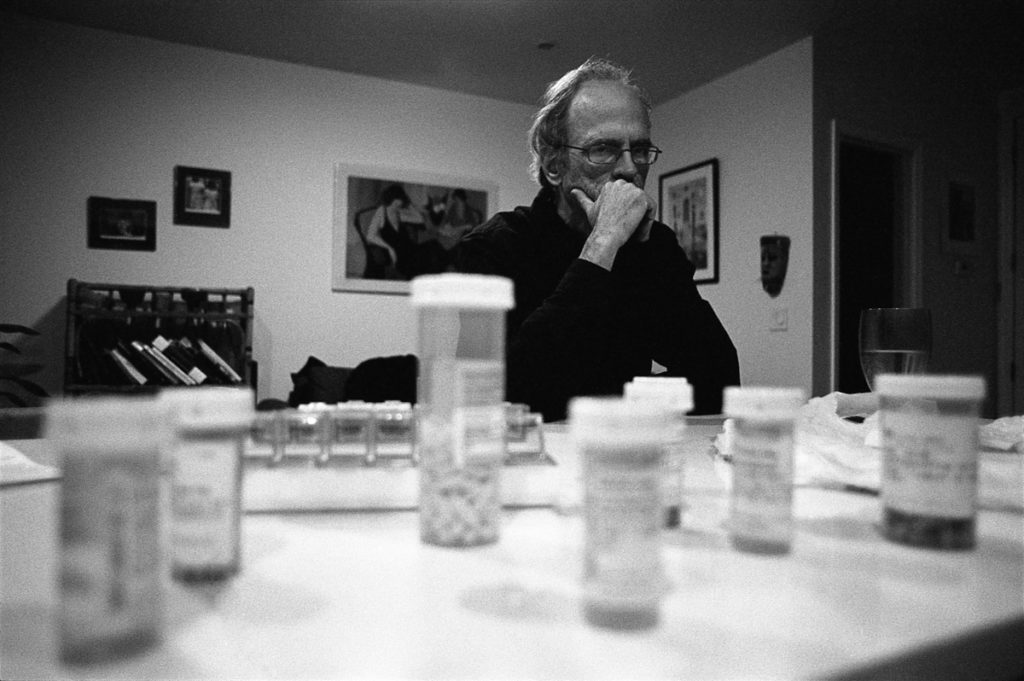

A soup of anti-anxiety and antipsychotic medications sit on the counter for sorting in November 2016. As the disease began to attack his personality and change his behavior, David became more erratic, plagued with fits of extreme confusion, increasingly accompanied by panic or rage. During these episodes, he often spewed curse words I had never before heard him utter. I grew up in a family where both he and my mom would make us kids wash our mouths with a bar of soap for swearing. Even when I was older, I noticed that he, more than my mom, was genuinely upset by foul language. David, always calm and good natured, was disappearing.

But, Cheney says, his dad has always been very supportive of him and his photography. “I would like to think that he would be proud of me.”

Subsets of the series have been published on two different sites. Feedback from viewers was intense, Cheney said.

“It was an exhausting amount of feedback. Either friends, friends of friends, people who were friends with my dad and strangers who reached out as well, saying how they were affected and moved.”

During his final week, we stayed with David 24 hours a day. Language had completely deteriorated so we looked to his eyes for recognition and clarity. There were many moments we thought might be his last. His chest would move rapidly and his breathing would rattle. Yet as the whole family moved close, his breathing would regulate. He remained periodically responsive and for good or for bad, our presence seemed to keep him alive.

“The most important thing that those images are able to put into the world: People can see that they are not alone,” Cheney said. “For those who don’t know anything about the disease . . . they can see how devastating it can be.”

The photo series of David is not currently on display anywhere. Cheney said he has some ideas for the future of the project, which are in progress. You can follow along for updates on his blog: CheneyOrr.com.